Ever wondered why your favourite language model tokenizers use G with dot above for tokens starting with spaces?

If you’ve ever tried inspecting the token strings instead of token ids, you might find those tokens starting with a space having their space converted into Ġ (U+0120, LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G WITH DOT ABOVE).

import transformers as hf

tknz = hf.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("openai-community/gpt2")

tknz("hello world!").tokens()

# ['hello', 'Ġworld', '!']No, OpenAI didn’t intend to use this Ġ to indicate putting some pressure on Google. The space character is encoded in ASCII/Unicode as U+0020 (SPACE), it’s actually offset by 0x100 or 256 to become Ġ.

But why offset it by 256?

Byte-level BPE

First let’s start with Byte Pair Encoding, or BPE. When we train a BPE tokenizer on a corpus, we start from merging characters. But what will happen if we want to tokenize characters unseen in the training corpus?

Let’s think it step by step. A character (like space, A or 文) is represented in the computer by a code value, which is just an integer number. This mapping from character to a code value is called a coded character set. Latin letters and common punctuations used in English fit perfectly into the ASCII set, which is a subset of Unicode. The code values are usually stored in the UTF-8 format. This format stores each number as a variable-length array of bytes.

Therefore, we can simply convert each charater to its UTF-8 format before doing the BPE merges1. We will be merging bytes, and this is byte-level BPE. Since we only have 256 different bytes in total, and these 256 bytes can represent every character within Unicode, as long as we keep all 256 bytes within the vocabulary, we will never have an unseen character.

UTF-8 Bytes and Byte-level Tokens

UTF-8 mapping is defined as follows. Notice that the 1-byte representations are strictly compatible with ASCII, and no code value is a substring of another code value.

# z, y, x, w, v, u are actual bytes in the codepoint.

U+ 0000 - U+ 007F | 0yyyzzzz

U+ 0080 - U+ 07FF | 110xxxyy 10yyzzzz

U+ 0800 - U+ FFFF | 1110wwww 10xxxxyy 10yyzzzz

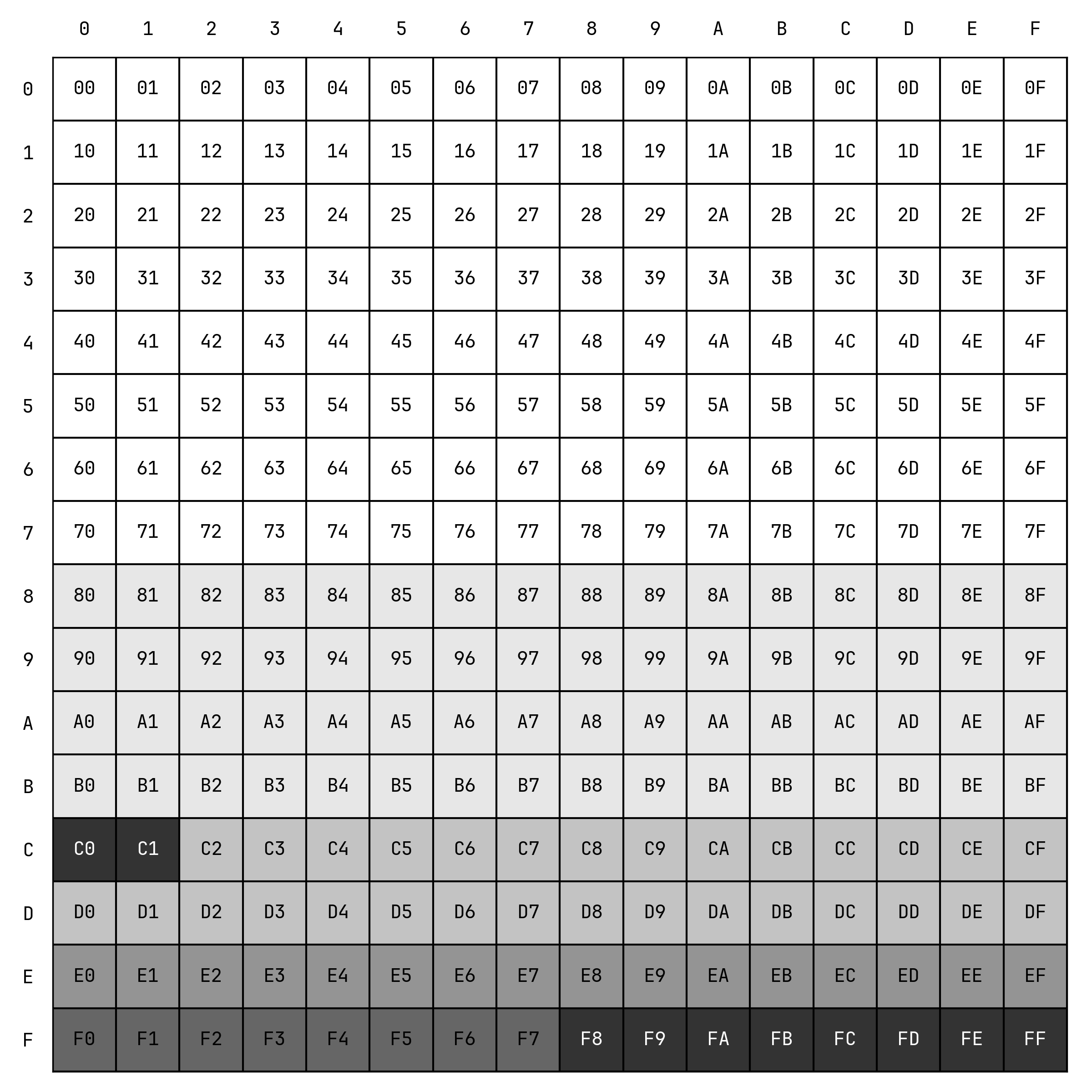

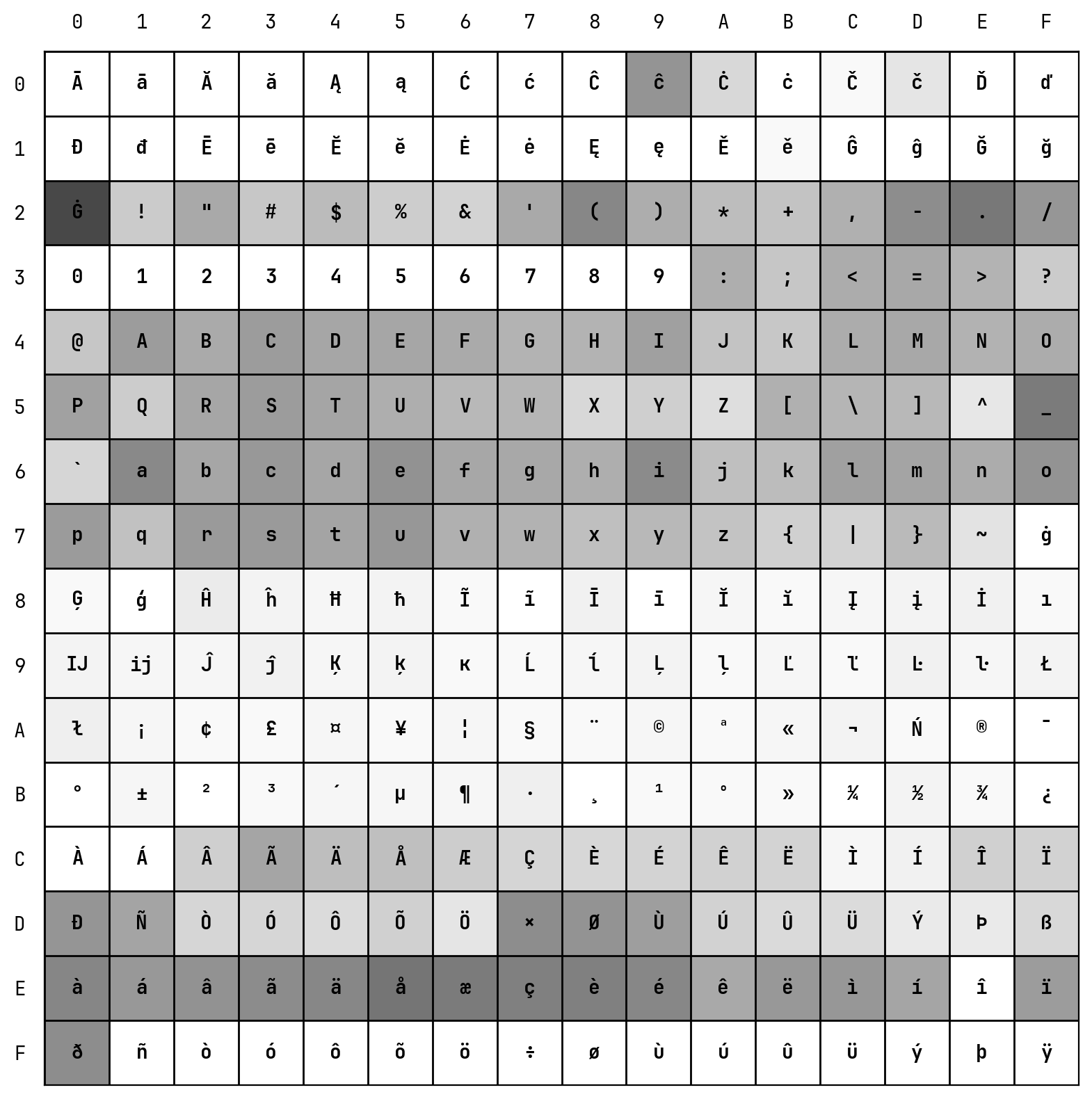

U+010000 - U+10FFFF | 11110uvv 10vvwwww 10xxxxyy 10yyzzzzActually not all 256 bytes are used. The first 128 points (0x00-0x7F) are 1-byte ASCII characters, the following 64 points (0x80-0xBF) are continuation bytes. The remaining 64 are leading bytes, mostly. The invalid ones are marked by black.

0xC0 and 0xC1 are forbidden, because a 2-byte UTF-8 starting with 0b110000. have 7 bits for actual values. That's exactly 0x00-0x7F which should have been represented using only 1 byte.

Besides, 0xF8 through 0xFF corresponds to VLAs of longer lengths, currently defined as illegal.

Return to BPE. In byte-level BPE we merge bytes, and create tokens that are byte arrays of variable lengths. However, not all these arrays are valid within UTF-8. Most English words are fine, since their tokens are always ASCII chaining together. But if we have only continuation bytes merging together, or leading bytes followed by too few continuation bytes, or continuation bytes followed by leading bytes, we get tokens that are not representable in UTF-8.

OpenAI’s Token Representation

Actually non-UTF-8 tokens are not a big problem, since individual tokens are usually not for humans to read. If your token sequence is encoded from a valid UTF-8, they will decode to UTF-8 for sure.

What if we really want to read these tokens? There’s actually an easier solution. If the token itself is a valid UTF-8 sequence, just decode it as UTF-8. Otherwise, escape it. Isn’t Python’s bytes doing this?

str(bytes([0xa0, 0x61]))

# b'\\xa0a'

# ^^^^^ -- the escape of 0xa0

# ^ -- 0x61 is `a`You are absolutely right! But OpenAI wants to do something cool in their GPT-2 tokenizer. They implemented a function called bytes_to_unicode to convert every byte into a printable character.

@lru_cache()

def bytes_to_unicode():

"""

Returns list of utf-8 byte and a corresponding list of unicode strings.

The reversible bpe codes work on unicode strings.

This means you need a large # of unicode characters in your vocab if you want to avoid UNKs.

When you're at something like a 10B token dataset you end up needing around 5K for decent coverage.

This is a signficant percentage of your normal, say, 32K bpe vocab.

To avoid that, we want lookup tables between utf-8 bytes and unicode strings.

And avoids mapping to whitespace/control characters the bpe code barfs on.

"""

bs = list(range(ord("!"), ord("~")+1))+list(range(ord("¡"), ord("¬")+1))+list(range(ord("®"), ord("ÿ")+1))

# ^

cs = bs[:]

n = 0

for b in range(2**8):

if b not in bs:

bs.append(b)

cs.append(2**8+n)

n += 1

cs = [chr(n) for n in cs]

return dict(zip(bs, cs))Turns out that their BPE algorithm works on strings underneath, not bytes. That’s why the whitespace and control characters break their BPE code. Urgh. But what is the mapping trying to do? How does it map every byte to be visible?

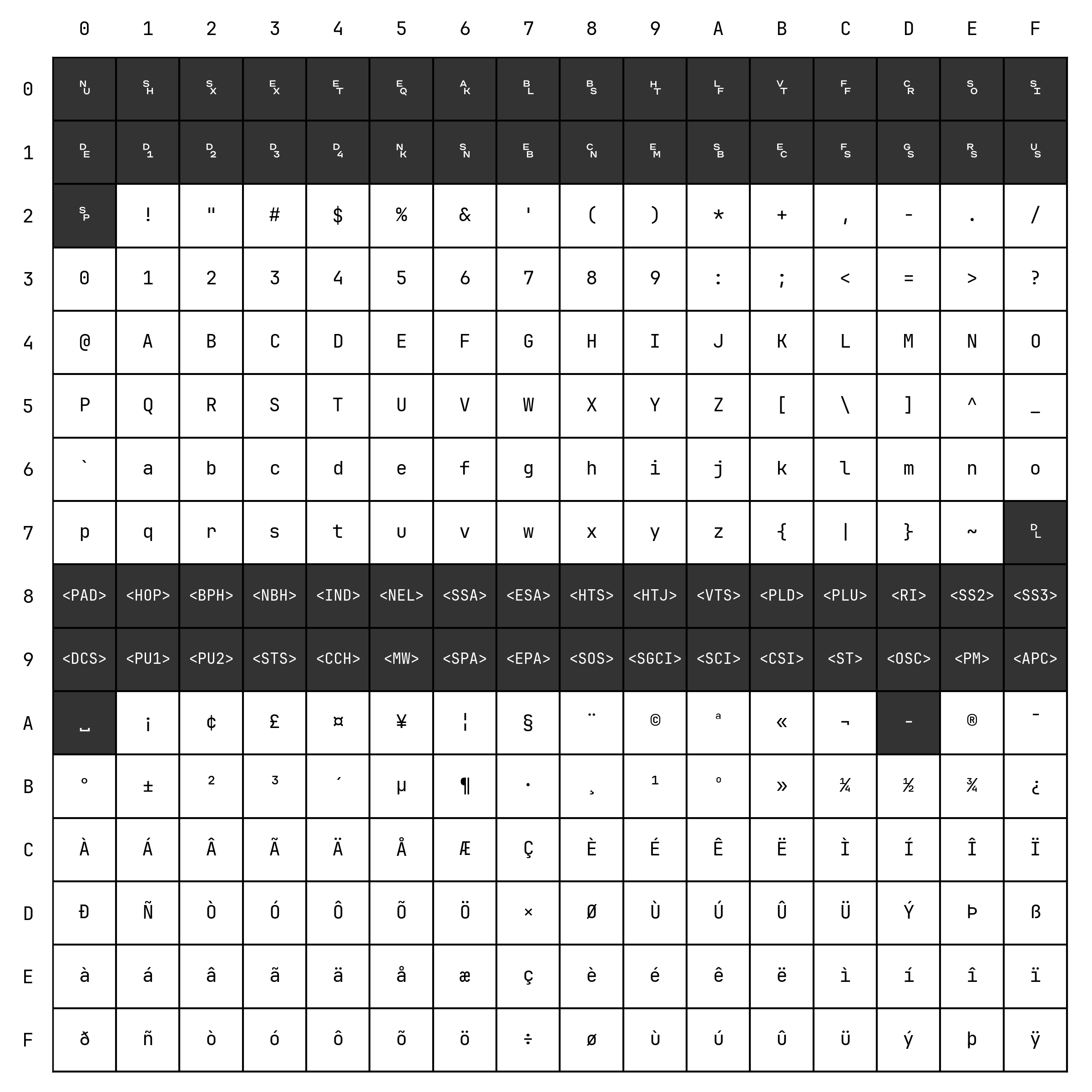

Let’s inspect the first 256 codepoints of Unicode, which corresponds to the first two blocks, Basic Latin and Latin-1 Supplement.

| Codepoints | Visible? | Description |

|---|---|---|

U+00 - U+1F | ❌ | Control characters known as C0. |

U+20 | ❌ | Space. |

U+21 - U+2F | ✅ | Punctuations, ! to /. |

U+30 - U+39 | ✅ | Arabic numerals, 0 to 9. |

U+3A - U+40 | ✅ | Punctuations, : to @. |

U+41 - U+5A | ✅ | Latin capital letters, A to Z. |

U+5B - U+60 | ✅ | Punctuations, [ to `. |

U+61 - U+7A | ✅ | Latin small letters, A to Z. |

U+7B - U+7E | ✅ | Punctuations, { to ~. |

U+7F | ❌ | Delete. |

U+80 - U+9F | ❌ | Control characters known as C1. |

U+A0 | ❌ | No-break space. |

U+A1 - U+AC | ✅ | Punctuations and symbols, ¡ to ¬. |

U+AD | ❌ | Soft hyphen. |

U+AE - U+BF | ✅ | Punctuations and symbols, ® to ¿. |

U+C0 - U+FF | ✅ | Extended Latin letters, À to ÿ, and also ×÷. |

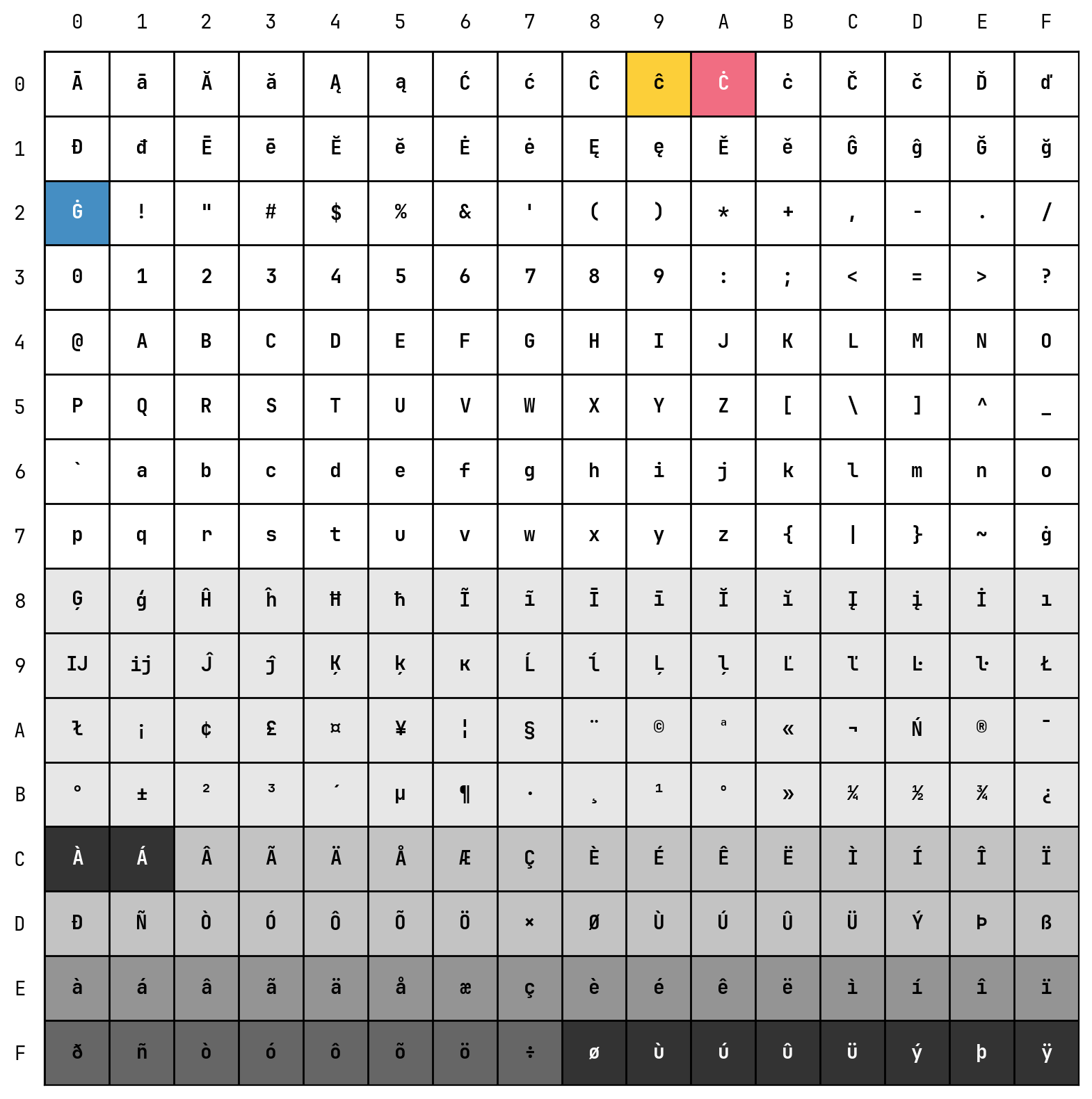

Then, how to visualize these invisible codepoints? We have Latin Extended A block from U+100 to U+17F. Just fill these blanks from that block! The following chart shows the result. Gray cells are those characters filled from Latin Extended A, and black cells are those illegal UTF-8 bytes.

Since space is U+20, and it’s UTF-8 representation is 0x20, it becomes Ġ. We borrow Latin Extended A letters until U+143, which is Ń. Because of this infill, the offset is not always 256. It can also be 0xA2 = 162 for bytes from 0x7F to 0xA0, and additionally 0xAD maps to U+143.

But wait, this representation schema is nevertheless visible, but is it really human-readable?

tknz = hf.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("Qwen/Qwen3-8B")

tknz("我是一个小型语言模型").tokens()

# ['æĪij', 'æĺ¯ä¸Ģ个', 'å°ıåŀĭ', 'è¯Ńè¨Ģ', '模åŀĭ']

tknz("Je suis un petit modèle de langage.").tokens()

# ['Je', 'Ġsuis', 'Ġun', 'Ġpetit', 'Ġmodèle', 'Ġde', 'Ġlang', 'age', '.']If you only cares about English, you will only encounter Ġ. If you work on CJK characters (notice that we are using Qwen’s tokenizer here), congratulations! Here’s a self-standing Python snippet to convert this representation to Python bytes-like string representation. Valid UTF-8 sequences are directly encoded to Unicode characters, invalid ones will be left as \\x00 raw bytes.

from typing import overload

@overload

def bpe_token_to_utf8(token_str: str | bytes, *, return_type: type[bytes]) -> bytes: ...

@overload

def bpe_token_to_utf8(token_str: str | bytes, *, return_type: type[str] = str) -> str: ...

def bpe_token_to_utf8(

token_str: str | bytes,

*,

return_type: type[str] | type[bytes] = str

) -> str | bytes:

"""

Converts a Byte-level Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)'s human readable token string back into

its original UTF-8 string or byte representation.

The input string is typically obtained via `PreTrainedTokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens`.

Notes:

- The token string may contain byte sequences incompatible with UTF-8

(representing unmerged bytes), displayed in `\\x` format.

- The conversion logic reverses the byte-to-unicode mapping used in [openai/gpt-2](https://github.com/openai/gpt-2)

documented in the `bytes_to_unicode` function.

Args:

token_str (str | bytes): The visualized BPE token string.

return_type (type): The desired output type (`str` or `bytes`). Defaults to `str`.

Returns:

str | bytes: The decoded UTF-8 string or bytes, depending on `return_type`.

Raises:

TypeError: If the input or return_type is invalid.

ValueError: If the input contains characters outside the expected BPE visualization range.

"""

if return_type not in (str, bytes):

raise TypeError(f"Expected output type to be bytes or str, got {return_type.__name__}")

if isinstance(token_str, str):

tokens = map(ord, token_str)

elif not isinstance(token_str, str):

raise TypeError(f"Expected input to be bytes or str, got {type(token_str).__name__}")

output_bytes = bytearray()

for codepoint in tokens:

if codepoint < 0x100:

# Standard ASCII/Latin-1 characters remain unchanged

pass

# Latin Ext-A range are remapped to unprintable characters

elif codepoint < 0x121:

# ? Non-printable range 1 (Control characters)

# ? Maps mapped unicode back to original bytes 0x00-0x20

# ? U+0100 -> U+0000 (Null)

# ? ...

# ? U+0120 -> U+0020 (Space)

codepoint -= 0x100

elif codepoint < 0x143:

# ? Non-printable range 2

# ? Maps mapped unicode back to original bytes 0x7F-0xA0

# ? U+0121 -> U+007F (Delete)

# ? ...

# ? U+0142 -> U+00A0 (Non-breaking space)

codepoint -= 0xA2

elif codepoint == 0x143:

# ? Non-printable range 3

# ? U+0143 -> U+00AD (Soft hyphen)

codepoint = 0xAD

else:

raise ValueError(

f"Unexpected character: {chr(codepoint)} in BPE Tokens (codepoint: U+{codepoint:04X})"

)

output_bytes.append(codepoint)

if return_type is bytes:

return bytes(output_bytes)

# return_type is str

return output_bytes.decode("utf-8", errors="backslashreplace")You might ask why don’t we just map Huggingface’s Tokenizer.decode2 over all token ids? It will map UTF-8 fragments to �, (U+FFFD, REPLACEMENT CHARACTER). This is mostly fine, but there will be fragments in long-tail text, where the raw byte is more informational than a rhombus.

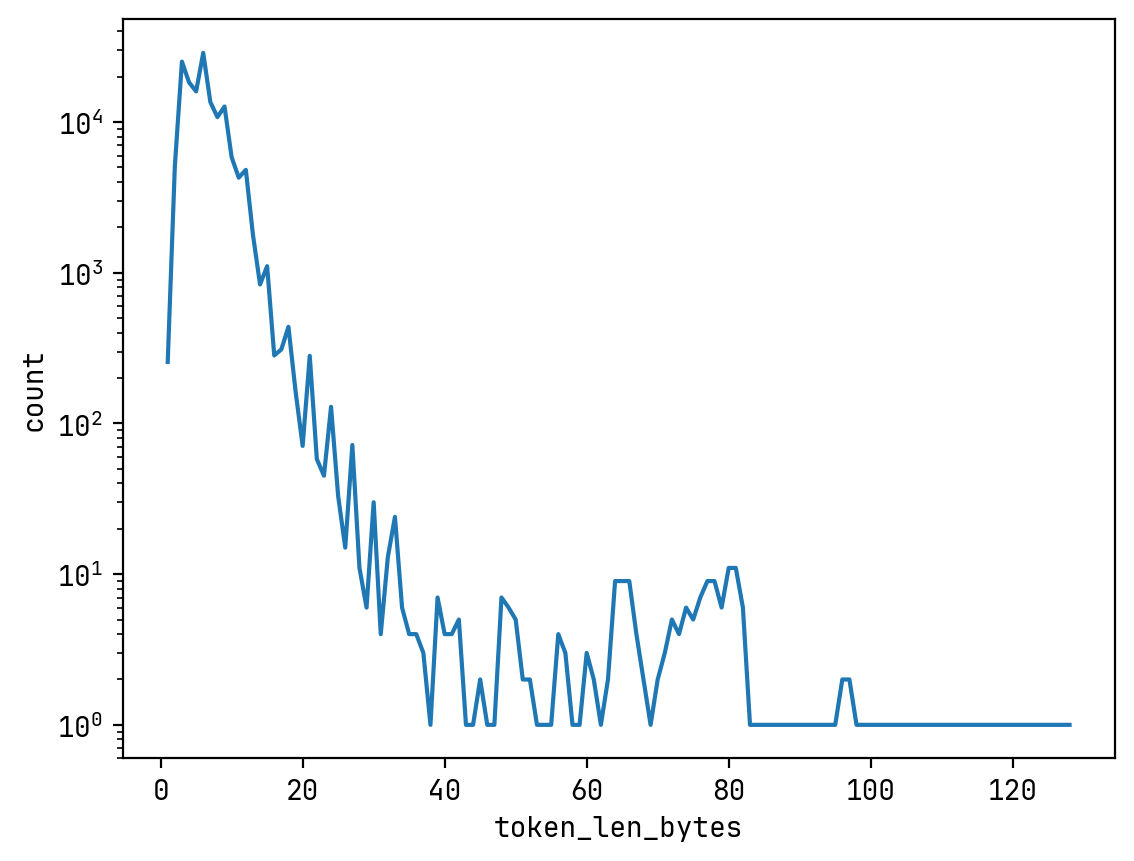

Analysis of Qwen 3 Tokenizer Vocabulary

The following plot shows the distribution of Qwen 3’s tokenizer vocabulary over byte lengths.

And the following heatmap shows the leading byte of every token within Qwen 3’s tokenizer vocabulary. Among 151669 tokens, 53021 starts with Ġ, the whitespace. Most CJK characters start with 0xE4 to 0xE9 in their UTF-8 representation, and we can see that 0xE4 to 0xE9 is also a hot region.

All 8,105 Chinese characters within their List of Commonly Used Standard Chinese Characters (《通用规范汉字表》) have their own dedicated tokens. 25,308 tokens start with a basic Chinese character within the CJK Unified Ideograph block (U+4E00-U+9FFF)3, among them 8,501 tokens contain only 1 character. No Chinese only tokens contain more than 4 characters.

The cases where a basic Chinese character follows or precedes a UTF-8 fragment are quite rare, each has around 20 occurences. However, there will certainly be characters be cut into multiple tokens. 12,053 basic characters are cut into two parts, 438 are cut into three. Among the fragments created by cutting basic characters, 0xE9 or é is the most common token encountered (in 469 characters’ tokenization), trailing by 0xB6 or ¶ (in 279 characters’ tokenization).

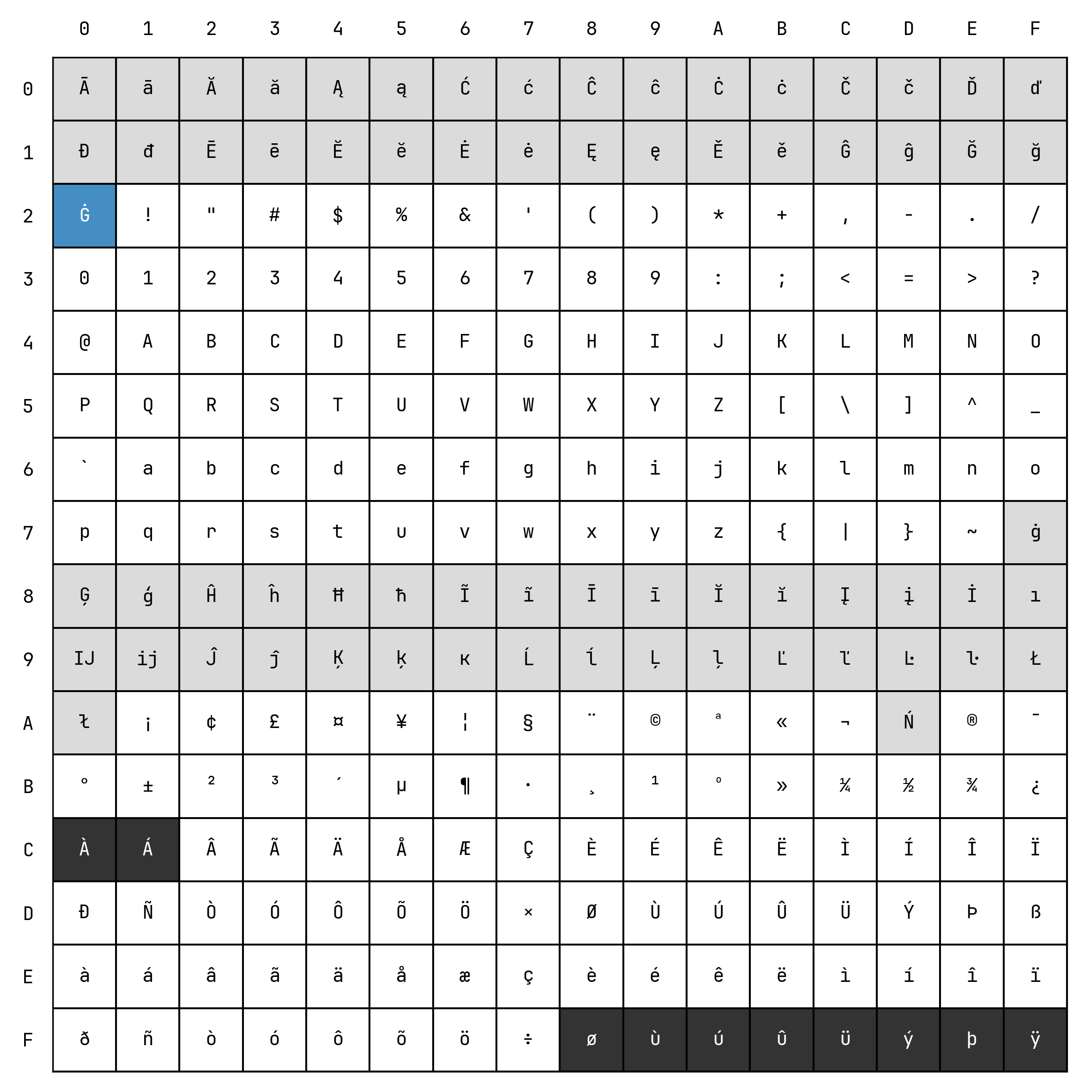

Token Representation Cheatsheet

Lastly, there’s a chart for you to decide which UTF-8 byte type do these BPE token representations correspond to. Specifically, Ġ, Ċ, ĉ correspond to whitespace, newline, and tab, marked in blue, red and yellow respectively.

Footnotes

-

Technically we don’t have to use the UTF-8 format, any integer representation should work. But UTF-8 is the de facto standard, so why not? ↩

-

According to the document, it’s essentially calling

Tokenizer.convert_tokens_to_stringon the BPE tokens. ↩ -

Note that only 7,832 common characters are in this block. ↩